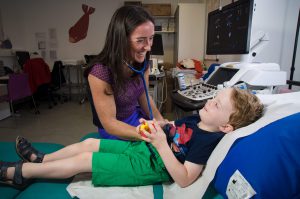

As part of my role as a paediatric and fetal cardiologist I see pregnant women in our fetal cardiology clinics in GOSH and the combined fetal medicine and fetal cardiology clinic at UCLH.

The advancement in scanning technology means that many congenital heart problems or fetal heart rate and rhythm issues, are picked up before the baby is born.

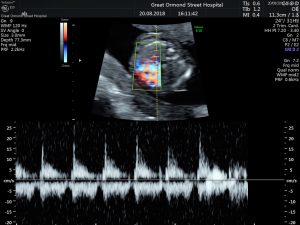

NORMAL FETAL HEART AT 20 WEEKS

Normal views of Aortic arch in 20 week fetus

In some cases we screen mothers in whom there is a known risk factor that puts their baby at an increased risk of a congenital heart defect, these include a family history of congenital heart disease, certain maternal diseases such as diabetes or certain connective tissue diseases. In addition findings on routine scanning and combined screening testing early in pregnancy may suggest an increased risk of congenital heart disease.

I understand it can be very worrying and distressing to be told there may be something wrong with your baby’s heart. Fetal cardiology provides expert evaluation and diagnosis of fetal heart defects. With explanation of and counseling about all treatment options. It then allows careful planning for your baby’s delivery. The parents can avail of a range of support services to help support the family before and after the baby’s delivery.

The optimal timing for fetal echocardiography is 18-20 weeks gestation. Sometimes if the fetus is in a good position, adequate images can be obtained earlier.

Normal fetal echocardiogram at 16 weeks gestation

NORMAL 4 CHAMBER HEART AT 16 WEEKS

NORMAL AORTIC ARCH 16 WEEKS